Negotiations at SCIC in deadlock

The interpreters held a General Assembly on 14 June 2024

The European Parliament has managed to integrate platform meetings into the working conditions. It has laid down fairly clear rules for participants’ microphones to ensure proper sound, and the workload takes account of the increased mental charge. Unfortunately, at SCIC, after almost a year, negotiations on this very subject have failed to reach a successful conclusion.

Since the negotiation meeting on February 2, and despite the request of the Interpreters’ Delegation, there has been no official negotiation meeting for 3.5 months.

Discussions had always based themselves on a draft text from the Interpreters’ Delegation, given that the hierarchy had not submitted a complete draft text. The solution proposed by the DI would meet the needs of SCIC, including Planning, would protect the health and safety of interpreters and meeting participants and, what’s more, would be more economical than the current rules (between September 23 and February 24, it would have saved over 2.2 million euros).

It was not until last Friday, May 24, that negotiations resumed.

One week before, the hierarchy had finally provided a draft text – but which “forgets” the achievements of the negotiations of 2 February, adds a “surprise” package of categories of meetings that would be exempted from the rules and includes a key provision (limitation of exposure in days per week) only for the pilot phase of 6 months.

It would seem that SCIC wishes to incorporate a new way of working (platform interpretation) without any other form of trial:

— Without guaranteeing the safety of employees (no guarantee of good sound, no guarantee of hearing health),

— Without really wishing to limit exposure (which is a second best solution anyway),

— Without taking into account the increased cognitive burden.

The Interpreters’ Delegation negotiated in good faith and made some more concessions to the hierarchy where it was able to do so.

The “final” text sent by the hierarchy does not show a willingness to succeed.

The trade unions support the Interpreters’ Delegation, which has requested a further negotiation meeting. The hope of reaching an agreement is now weak. A resolution to this effect was passed at its General Assembly.

But it is clearly the solution that would be preferable for all concerned.

We want to avoid that solutions in this case involve social action. We always advocate problem-solving through social dialogue.

The General Assembly of Staff Interpreters of DG SCIC met on 14 June 2002.

Resolution adopted:

- Deplores the decision by the Director General of DG SCIC to unilaterally break negotiations and impose working conditions on platforms in disregard of social dialogue.

- Expresses their determination to continue providing high-quality interpretation and contribute to DG SCIC remaining both a viable and sustainable public service and an attractive employer with working conditions comparable to other institutions. Quality, reliability and safety are impossible without safe sound.

- Confirms that working conditions on platforms must guarantee auditory health and safety for interpreters factoring in cognitive load, pursuant to article 13 of the European Charter of

Fundamental Rights, Council Directive 89/391, and articles 5 and 6 of Commission Decision C (2006). - Notes that the European Parliament and Court of Justice have introduced Sound Protocols

including use of approved peripherals as a condition sine qua non for interpreters to do their job safely. - Deplores that the CPPT Recommendations published on February 16th, 2023, have still not been implemented a year later.

- Demands equality of treatment affording the same level of protection to interpreters in SCIC as in other institutions.

- Contends that a new technology such as Simultaneous Delivery Platforms cannot be deployed before a risk analysis is conducted and a complete, consolidated, and reliable register of cases of auditory pathologies reported by interpreters is established. Neither condition is currently met, and both are legal obligations.

- Considers that in the absence of proof that platforms are safe for interpreters, exposure levels should not be expanded beyond current levels. (Precautionary principle).

- Mandates the Interpreters’ Delegation to pre-emptively prepare an awareness raising campaign to contribute decisively to behavioural change in the use of approved peripherals with the backdrop of potential interruptions of service so that it comes as no surprise to our clients.

- Calls on management to go back to the negotiating table.

- Confirms the Delegation’s negotiation mandate in its entirety.

- Mandates the Interpreters’ Delegation, in the event of non-resumption of negotiations, to call a referendum to decide whether to pursue industrial action in hybrid meetings. The industrial action would consist in a work-to-rule approach, with no interpretation of distant participants in all simultaneous hybrid meetings on Interactio.

- In the event of a positive referendum, mandates the Interpreters’ Delegation as the elected

representative of all SCIC staff interpreters to contact the trade unions and request they register a strike action notice with a view to bringing Management back to the negotiation table and reach a balanced agreement acceptable for both parties.

Interpreters’ hearing health

Detection of work-related accidents reveals risks that are not sufficiently taken into account

In recent months, our organisation has helped several interpreters with cases of hearing problems caused by the use of sound equipment (headsets, microphones, sound platforms) in the course of their work. U4U has also played an active role in the social dialogue aimed at guaranteeing good working conditions for interpreters at the European Parliament and the Commission.

The recent recognition of several work-related accidents related to both acoustic shock and feedback marks an important stage in our fight, in collaboration with other trade unions and the interpreters’ delegation, for a multidimensional approach to this phenomenon. We will therefore continue to fight for fair compensation for the incapacity for work and damage to health suffered by interpreters, but also for the strengthening of preventive measures, the introduction of risk studies carried out at a professional level and the modernisation of sound systems.

It should be noted that although these particular risks primarily concern interpreters, they may also affect all our colleagues, as the use of headsets and microphones has become much more widespread since the spread of teleworking and remote meetings.

We will therefore continue to monitor this issue closely.

The acoustic roots of “Zoom fatigue” – 2nd part : solutions

The problematic sound of videoconferences and its consequences on stress and hearing health is a subject U4U has taken up since the pandemic. It is relevant especially for interpreters, but also for all those who have videoconferences as a tool in their daily lives.

In our last edition, we analyzed the highly processed sound of these conferences as source of the problem.

Today, we present several solutions.

An article by Andrea Caniato, voice consultant, certified voice trainer (Applied Physiology of the Voice) and EU accredited conference interpreter.

Videoconferencing platforms are designed to manipulate and alter by default the way you sound. Many people, including an embarrassingly high number of audiovisual professionals, still believe that the low quality of “internet sound” is due to the internet being unstable and to connectivity problems. However, good-quality sound does not use much bandwidth[1] and it is readily achievable in this day and age. The real reason why video calls sound shallow, distant, flat and unpleasant has been explained above and it has to do with the way platforms are designed (noise suppression, automatic gain control, unwarranted low-bitrate policies) and the type of microphones used to join online meetings: microphones built into laptops and mobile devices, videoconferencing headsets with boom microphones (including “recommended” models), centre-table microphones in videoconference rooms and the like. All of the above are designed to “improve” or “optimize” speech. The idea of improving and optimizing a voice might understandably seem desirable to the layperson, so huge amounts of new devices are sold every day to satisfy this artificially-induced need. But 95% of this processing is unnecessary and unwarranted since it creates more problems than it solves. Sound is a bit like fresh fish: its quality can only be preserved by a well-functioning “cold chain”, not “improved” or restored after it has been damaged. If a noise-filtered, AI-engineered signal will often ensure your voice is heard even if you are not using the right equipment, a natural and more faithful reproduction of your real voice will encourage people to actually listen to what you have to say.

But is high-quality sound possible on the internet?

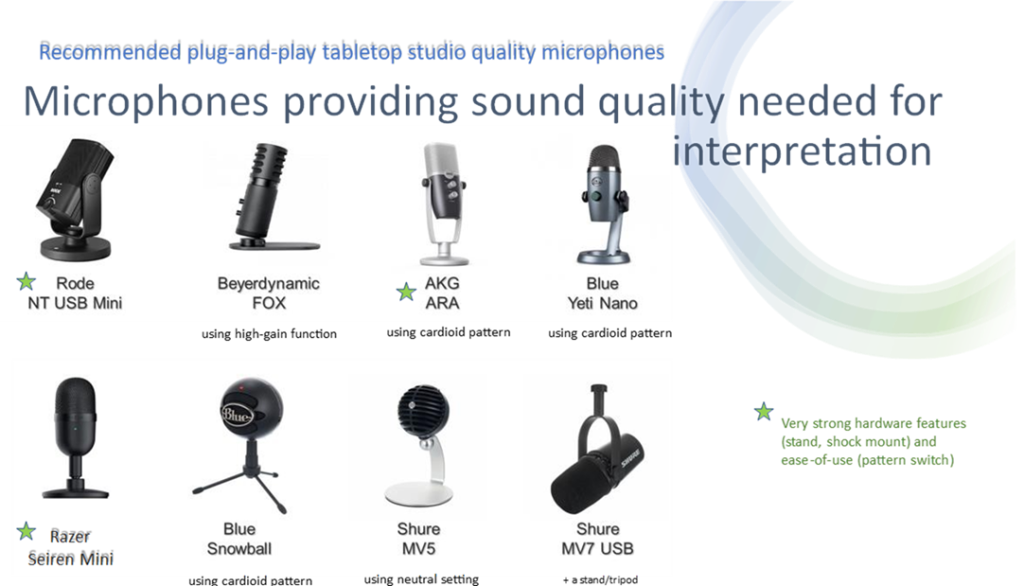

The answer is yes. It is both possible and not particularly difficult. All you need to do is tweak the right settings on a suitable videoconferencing platform, and use a real, plug-and-play, standalone podcasting microphone. Satisfactory solutions start from as little as 25 € and are abundantly available from any online store.

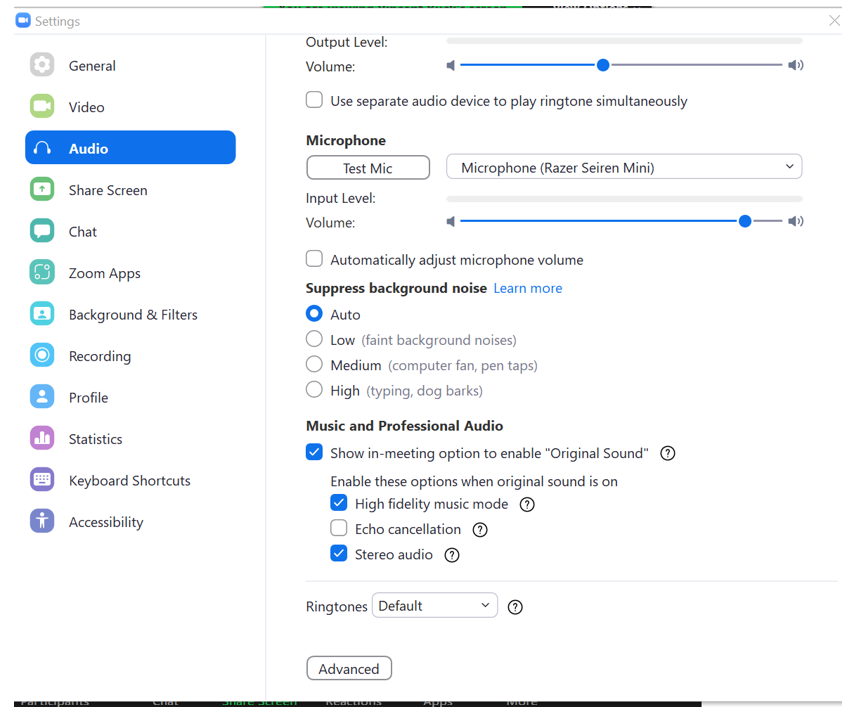

Let’s start with the platform. In order to make your actual voice is heard in high definition, you need to be able to deactivate the default settings that trigger undesirable processing. Not all videoconferencing platforms allow this, as they seem to assume you are incapable of connecting a decent microphone into your USB socket.

Here is a list of platforms that will enable broadcast-quality sound:

1) By far the best performer: Zoom, in Hi-fi Mode.

When the Hifi Mode is activated in Zoom, Zoom will not process your input and broadcast the sound exactly as it is picked up by your microphone. This function was developed during the summer of 2020 to allow prestigious music colleges in the US to teach music during the Covid-19 lockdown. Once you have a decent microphone connected, you will be able to sound like you would on the TV or, if you are using a podcasting microphone (podcasting microphones start from as little as 30 €), like you would on the radio. It is genuinely that good.

The Hifi function is available free of charge to all users of an up-to-date Zoom app for Windows or Mac. It will not work from your internet browser. It has successfully been tested for over 3 years in labs and during thousands of webinars and there are absolutely no contraindications even as far as home use is concerned. It will not require too much bandwidth (video is what actually uses your bandwidth, not audio), it will not crash your computer, you will not have to sound-proof your office in order to use it[2]. Speaking at 30 cm from the microphone will automatically reduce the impact of any background noise in your room by around 90%, and whatever background noise ends up being picked up by the microphone[3], it will not annoy your listeners because it will not be made louder and more aggressive by the AI-processing you have deactivated.

Zoom HiFi is also available from mobile devices, but its performance does not compare with what can be obtained using a personal computer.

Here are the boxes you need to have checked and unchecked under “Audio Settings” :

Please note that all forms of automatic gain control, noise suppression etc. need to be deactivated or neutralized by unticking them or setting them on “auto”.

Please also note that the best results are achieved if you are using headphones (of any type) instead of computer speakers, as this will allow you to keep “echo cancellation” deactivated and further improve the quality of the sound you make.

Please also remember that if you plug a poor-sounding microphone (earbuds, integrated iPad microphone, call-centre type headset etc.) into Zoom HiFi, you will simply hear the poor sound made by your unsuitable microphone. Please also bear in mind that an “Original Sound” button will appear on the main call screen once “Music Mode” is on. You need to press that button as well to activate Hi-Fi sound properly.

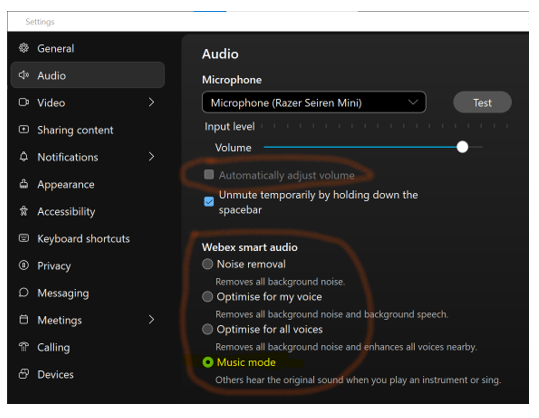

2) A worthy runner-up to Zoom HiFi: Webex in Music Mode

Music mode was introduced to Cisco Webex around one year ago. Although it does not sound as impressively good as Zoom HiFi, it is still worth activating if you want to sound like a real human being. The result is perfectly acceptable when a decent microphone is used. Activating music mode on Webex is also easier than it is on Zoom: just make sure the automatic gain control function is deactivated and tick the “Music Mode” box. Under “advanced settings, make sure you are bypassing your computer’s audio drivers completely.

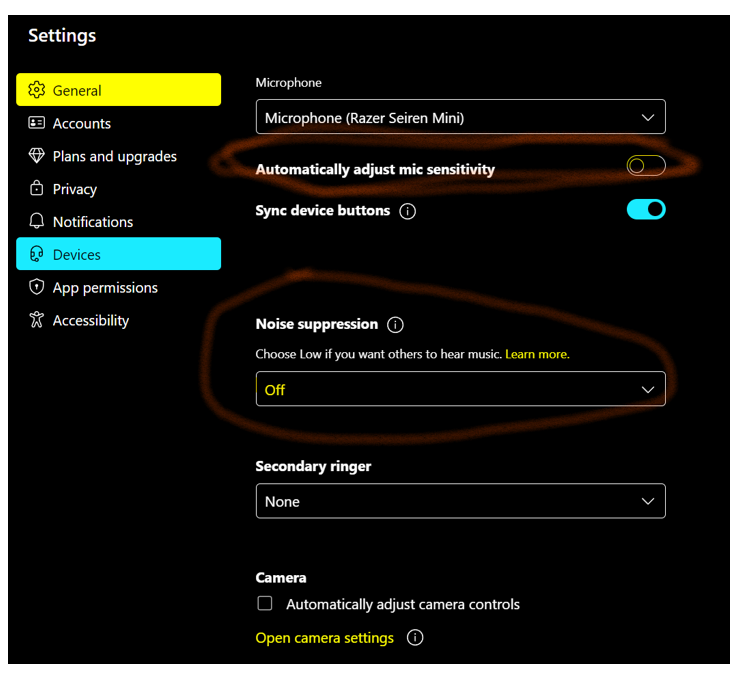

3) Promising the moon, delivering much less because YOUR connection is never good enough: MS Teams

MS Teams introduced a new High Fidelity Music mode towards the end of 2021 and claims that if this mode is activated, a 32kHz sampling rate at 128kbps is made available “when network bandwidth allows”. But when the network doesn’t allow, “the bitrate can be reduced to as low as 48kbps and Teams still produces good-quality audio” (source: https://support.microsoft.com). Listening tests evidence that unlike Zoom and Webex, MSTeams will probably never consider bandwdith to be sufficient to bring quality up to the required bitrate. Even when a powerful connection and a very good microphone are used, “high-fidelity” MSTeams will sound better than “basic” MS Teams, but does absolutely not compare with Zoom Hi-Fi (not even with Webex). Noise-suppressing algorithms are removed and autogain appears no longer to be working, so the option is definitely worth activating (with a couple of limitations: see below), but if you want other people to enjoy your presentation, Teams is not an option.

Blaming lower quality sound on the performance of users’ connections has long been a popular excuse in the videoconferencing business. And yet video transmission uses up 7-10 times more bandwidth than sound, so if the problem really were on the participant’s end, most people would not be able to use their webcams either… Moreover, 48kbps is hardly compatible with “good-quality audio”.

The high-fidelity music mode is found under Settings> Devices> High-fidelity music mode, but only if you have a MSTeams client AND a paid corporate license. If you do not have a paid license, a “music mode” pop-up will briefly appear on your screen if MSTeams identifies “music” in your room (!!!).

MS Teams basically makes a “better sound” option available, but only if you really know where to go looking for it, only if you have a paid license… and only if your connection is more powerful than NASA’s. In a nutshell, MS Teams does not really want you to use their hi-function, and sound quality is clearly not a priority in the MS Teams environment.

4) A bare pass: Skype

Recent versions of Skype allow users to deactivate background noise suppression and autogain, which is a good start. Bitrate is probably nothing exceptional. Deactivating those 2 functions (under advanced options) improves sound quality. Skype’s output does not compare with Zoom and Webex, but at least heavy filtering can be deactivated, which remarkably reduces signal degradation.

What about Google Meet and the rest?

On Meet and other platforms, there is not much more you can do than use a better microphone (microphones are discussed below) so as at least to reduce the amount of processing your voice is subjected to.

When you use Google Meet and basic MS Teams (and Webex, etc) your voice is bound to sound muffled and unnatural.

A good platform like Zoom HiFi will allow you to hear the actual quality of the microphone you are using. Let’s have a look at which affordable and user-friendly microphones do your timbre justice in the videoconferencing environment.

MICROPHONES

What microphones should be avoided?

The built-in microphone of your computer / smartphone / iPhone / iPad / Macbook (yes, even Macbook) webcam microphones (with a couple of exceptions), smartphone and iPhone earbuds (and all Blueetooth microphones), headsets with boom microphones (especially USB) and, above all, the microphones installed in corporate videoconference rooms (even if they were sold to your company as “miraculous”) should be avoided at all costs. They are designed with telephone quality in mind, and they actively and heavily process your voice in the ways discussed in this article (noise suppression, aggressive equalization, dynamic range compression etc). There is a huge amount of marketing behind call-centre type headsets with boom microphones and microphone arrays on the ceiling of corporate videoconference rooms. Therefore, the fact that YouTubers are recommending them, IT people are vetting them, your employer is buying you one and that all of your colleagues are convinced that they are excellent is not entirely surprising. But it is still completely wrong.

When you use these microphones, your audience will see you on screen the way they would see you on the television (possibly in high definition), but they will hear you sounding like a call-centre employee on the phone – albeit louder.

Which microphone should you use to make sure people hear your real voice?

The easiest solution is a USB podcasting or desktop microphone. This type of microphone is not intended to be used in a call-centre-type environment (where dozens of people are sitting in close proximity and simultaneously making telephone calls, from the crowded waiting area of an airport or from the terrace of a bar. This being said, these are also not the sorts of places you should be addressing a videoconference from – not if your personal image and your content are of any importance to you.

USB podcasting microphones are recording microphones, so they are designed with radio quality in mind, to pick-up the sound of your voice as faithfully as possible, without manipulating it in any significant way. Anyone can use them. All you need to do is plug one into your USB socket and select it as the default microphone in your videoconferencing platform.

Manufacturing a good microphone is not particularly expensive, and so a budget as low as 30 € will suffice to buy a microphone that will make you sound better than a talk-show host. More sophisticated microphones will cost you around 50€ and microphones giving you the equivalent of recording-studio quality will cost you between 70 and 100 €. Brands like Seiren, RØDE, Shure, AKG etc. have excellent solutions below 100 €. All you need to do is look up “podcasting microphone” in your favourite webstore.

Recommendations on specific models and makes can be found here.

USB lapel microphones are also an interesting option. They are designed to be used in interviews and broadcasting situations, so their input remains unprocessed. The USB connector will bypass your computer’s sound card and sound drivers (which are a potential source of audio manipulation). The microphone is barely visible on camera (no more visible than on the tie or neckline of a TV anchor), which will make you appear more professional. Depending on your budget and if used on Zoom (HiFi), a USB lapel microphone will give you a reasonable, perhaps even perfect equivalent of TV sound. A decent solution from a reputable brand like Sennheiser – one that enables sound quality worthy of a prime-time TV show – will cost you no more than 70€.

This type of microphone is extremely lightweight, it fits in a pouch and it is therefore very easy to carry with you if you are travelling.

Like all other types of microphones, including headset microphones[4], lapel microphones need correct placement in order to perform at their best.

[1] Excellent quality audio uses up around 10% of the bandwidth required by decent video. 96Kbps are sufficient to deliver an excellent and natural-sounding representation of a human voice and even musical instruments. A low-performing internet connection with as little as 1mbps of upload speed can broadcast excellent quality audio and video.

[2] Even if platforms insist that a sound-proof environment and a highly professional microphone are necessary to switch to their “music modes and warn users that “voice” and “speech” are better if processed by their algorithms years of practice and dozens of webinars clearly show that none of that is actually necessary. Speech processing via DSP is probably being pushed to optimize the performance of to speech-to-text engines.

[3] The “inverse square law”: https://audiouniversityonline.com/inverse-square-law-of-sound/

[4] One of the reasons why center-table microphones, headset microphones and microphones built into computers and mobile devices are heavily processed by AI-algorithms is that they are intended for incorrect use: when the microphone is kept 50 cm (or more) away from your mouth, or very close to your lips, the chances of it picking up a lot of unwanted signal are extremely high, hence the need to overprocess its output.

The acoustic roots of “Zoom fatigue”

The Covid19 pandemic has permanently reshaped office life. Introduced as a sort of emergency patch in order to keep companies and institutions working during lockdown, frequent use of videoconferencing tools has become part of the “new normal”. An ability to participate in remote or hybrid meetings via Zoom, Teams, Meet etc. reduces the need to travel, saves time and affords unprecedented access to business partners, colleagues and audiences far and wide. On paper, the potential is huge: videoconferencing allows people to fit many more meetings into their schedule, without actually leaving their office. In quantitative terms, you can get “more work done in less time”. And if you are teleworking, you can do so even from the comfort of your own home. Less traveling, less commuting, possibly more time for yourself and your family: videoconferencing is, ostensibly, a sure-fire way of improving your well-being and your work-life balance.

Yet, many videoconferencing participants’ experience of online meetings is unpleasant and tiring, and scientists are warning that “Zoom fatigue” may have serious consequences for human health, including burnout[1]. Numerous attempts have been made to explain the causes of videoconferencing fatigue, mainly based on cognitive / emotional distress and frustration due to the lack of eye contact, diminished or non-existent access to visual cues and body language, multitasking, lack of (or unnatural exposure to) other types of visual information being just some examples[2]. Under this visually oriented, cognitive perspective, the videoconferencing environment does not properly satisfy the basic, innate requirements for effective communication between human beings, which generates subconscious frustration. Frustration leads to an adverse emotional response and negative emotions, which, in turn, generate stress.

This way of explaining the problem has three major shortcomings:

a) As it is based on the media naturalness theory[3], it tends to reduce the non-verbal aspects of communication to merely visual elements for conveying emotions and creating a rapport between people. It therefore focuses on visual aspects such as eye contact, facial expressions and body language (and the absence thereof during videoconferences) and visual feedback (participants apparently feeling alienated by the sight of their own face on the screen), compounded by additional stress factors such as multitasking or asynchronicity due to system latency.

b) It considers chronic fatigue, stress and burnout as the almost exclusive potential outcomes of frequent exposure to videoconferencing.

c) It fails to explain why the same factors, or similar combinations thereof, do not lead to similar outcomes in other settings: For instance, listening to a radio programme also involves the total absence of body language, visual cues, facial expressions. Listeners typically engage in other tasks while listening to it (ironing, dishwashing, driving, cleaning, working out…), but exposure to a radio programme while performing other tasks does not appear to generate stress. Likewise, exchanging emails or writing letters involves huge, noticeable latencies (hours, days, weeks), no body language and possibly a great deal of frustration if no answer is received, but the concept of “correspondence fatigue” has never become mainstream and is not known in the scientific literature. Watching YouTube tutorials or livecasts also involves micro-latency issues (most YouTubers are very slightly out of sync), an inability to interact (a crowded chat is all you have available during a YouTube or Facebook livestream) and the absence of eye contact when the speaker is not looking directly into the camera, but “YouTube fatigue” has not become an issue either, notwithstanding its popularity and widespread use.

Faulty as this attempt to explain fatigue might be, videoconferencing stress is real and its impacts on the human nervous system have been finally proven and described by a study recently published on Nature. A team of Austrian researchers has convincingly shown that mere passive exposure (no bi-directional communication, no interaction) to less than 1 hour of videoconferencing (e.g. a university lecture) causes measurable stress and fight-or-flight reactions not seen in subjects exposed to the same lesson in face-to-face mode[4]. Significantly, these results were produced in a quiet, stress-free and controlled laboratory environment, where exposure to a videoconference call was the only potential stressor.

This means that there is something about videoconferencing that inherently causes brain fatigue and measurable autonomic-system activity, typically seen when human beings perceive the presence of a threat. This happens even with passive exposure to situations where interaction and multitasking are not required – which would rule out frustrated expectations of interaction, multitasking, eye-contact and the like as a potential source of cognitive and emotional stress.

But what threat is the autonomic nervous system reacting to? And is this threat real or imaginary?

Some light on this question can be shed by focusing on a usually overlooked variable. It is typical of videoconferencing environments and virtually absent from other, more professional forms of broadcasting and from face-to-face interaction that both do not seem to cause any stress to recipients. This factor is the presence of degraded and heavily manipulated audio signals.

Though most people (and research teams) have so far failed to notice this, videoconference audio is highly unnatural and often heavily processed. Some of the key factors behind degraded videoconferencing sound have already been proven to:

a) cause measurable stress reactions in both human beings and test animals, even when these factors are taken individually;

b) not to be of a visual, cognitive or relational nature.

Let’s take a look at these stressors:

“Poor sound”.

In a study published during the early 2000s, Wilson, Gillian & Sasse[5] showed how different types of audio degradation elicited different reactions in test subjects. Some were psychological only, others were neurophysiological.

On the one hand, the sound defects typically caused by poor connectivity or network issues (packet loss) and resulting in loss of speech intelligibility of content (missing syllables, words, phrases or sentences) were reported as annoying and unpleasant by test subjects, but they failed to unleash any significant physiological stress reaction. On the other hand, audio degradation caused by low-quality microphones and “loud sound” was hardly noticed by test subjects and did not therefore result in any “cognitive” complaints, but it did cause measurable fight-or-flight reactions in participants. Their nervous systems were clearly perceiving a threat that their conscious mind failed to notice and identify, even though the laboratory task was minimally engaging and did not involve any real cognitive or relational effort.

A significant impact on the human nervous system could therefore be measured as a consequence of stimuli that did not reach the consciousness of test subjects and did not cause any cognitive or psychological reaction.

Fried guinea pig brains

A recent experiment conducted by Professor Paul Avan’s team at the Institut Pasteur[6] has shown how heavily processed digital sound (in this case, heavy dynamic range compression) can literally destroy the hearing system circuitry in the brain stem of test animals at listening levels that did not cause any irreversible brain stem damage in animals exposed to far less processed signals. The middle-ear reflex (the mechanism that protects the ear from loud sound) of animals exposed to heavy dynamic range compression could no longer function properly after the experiment had been completed.

Dynamic range compression is a form of digital audio processing that can be used to “inflate” sound and to engineer a sense of perceptual loudness, while not raising peak levels.

Tinnitus at the dentist’s

Dentists are particularly exposed to tinnitus and hearing loss, owing to the noise made by dental drills and the like. Studies on these drills have mostly failed to detect the presence of emissions exceeding safe limits, and dentists’ practices are usually not experienced as loud places by patients. So how are hand-held devices damaging the ears of dentists? By looking into the qualitative aspects of dental drill noise, one research team[7] has found that the noise made by these devices is concentrated in very specific ranges of the audible spectrum (2k-6kHz). Incidentally, the human auditory system is particularly sensitive to high-frequency vibration (especially in the 3k-5kHz). Opera singers leverage resonance in those areas (especially 3kHz) to override the background sound of orchestras, and infant voices deliver more energy than adult voices in the same area (especially around 4kHz) in order to attract attention. Shouting also increases energy in the same area of the audible spectrum. Delivering higher concentrations of acoustic energy around 3k-4kHz is a sure-fire way of attracting attention by causing alarm – and, to the nervous system of human beings, alarm means stress. The human inner ear has evolved to be particularly sensitive to those frequency bands. Specialized sensors are both very abundant. They are also easily damaged by acoustic trauma, which is usually caused by occasional exposure to extremely loud spikes (jet engines, gunshot) or frequent exposure over time to large average doses of noise in loud environments (e.g. factories, construction sites).

It would appear that concentrating acoustic energy in sensitive frequency bands may harm the human ear even at much lower levels than those that, to date, have been considered unsafe. Interestingly, a study conducted in Sweden has recently found that pre-school teachers exposed to theoretically safe daily doses (75-85dB) of infant voices have a higher incidence of hyperacusis[8].

But what does videoconferencing have in common with crying children, opera singers, dental drills, overcompressed music or high average dB exposure? Is videoconferencing sound “loud” or “operatic”? Do videoconference participants shout or use dental drills during calls? And, if a psycho-cognitive model of the problem is applied, does videoconference sound lack any of the crucial elements of human communication?

Videoconferencing sound is aggressive

Not many people notice this, but the voices of videoconferencing participants and the noise they can occasionally make near their devices are extremely artificial. Videoconferencing audio is anything but natural-sounding. It’s usually piercing, metallic, slightly (or very) robotic, artificial and often muffled, even when connection speeds are very high and video is HD. In other words, videoconference sound is intrinsically “noisy”. Multiple tests of videoconferencing platforms have shown how the widespread use of AI algorithms that “optimize” voice, remove background noise, keep your voice at a constant level, regardless of how far you are swaying away from the microphone, and prevent audio feedback introduce sizeable amounts of harmonic distortion, muffle sound and reduce intelligibility. Noise-filtering algorithms have the biggest detrimental impact, since getting rid of background noise live is an AI-driven guessing game and doing it without compromising the quality of the signal (i.e. by degrading timbre) is virtually impossible. The more aggressive the filtering, the heavier the muffling, distorting and robotizing impact on the speaker’s voice. Noise filters also have a widely recognized impact on speech intelligibility, which is why additional AI algorithms are used to compensate for loss of intelligibility by engineering a sense of perceptual loudness in the signal in order for it to stand out against the background noise and make the most of the receiver’s usually undersized and underperforming computer speakers or headphones.

Put in oversimplified, layman’s terms, this is typically done in 3 ways:

a) by equalizing the signal aggressively and raising levels in a targeted manner: the signal is manipulated so that proportionally more dB (often even + 20, 25dB) are assigned to ranges of the audible spectrum where the human ear is particularly sensitive: the notorious 3k-5kHz area. This makes the sound piercing and metallic, without making it exceed theoretically safe dB levels, and clearly punches the auditory system where it is less defended. This is the AI-generated equivalent of dental-drill noise.

b) by raising softer components at a microscopic level so that they become louder than they would normally be. While the overall permissible peak dB levels are not exceeded, the average dB content of the signal is increased, while energy is concentrated in very sensitive ranges of the inner ear, as shown above. The “dental drill” is never softer than a certain level, determined by an AI algorithm programmed (or operating autonomously) without much understanding of how the human hearing system is supposed to function. This type of processing is a form of aggressive dynamic range compression (not to be confused with data compression, as in mp3) also known as “upward compression”. Measurements have shown that exposure to dynamic ranges not exceeding 10 dB is frequent in the videoconferencing and hybrid setting, which means that the sound is flat and the auditory system (especially some of its softer spots) is kept under constant, unrelenting pressure. The laws of physics are very clear regarding the effects of constant pressure concentrated in a small surface area: pressure does not need to be heavy to dig a hole if it is applied constantly and for long enough. Bed ulcers in bed-ridden hospital patients are an excellent example for visualizing how this type of signal can damage the auditory system. Published research, moreover, shows that the human auditory system activates protective reflexes (the stapedial reflex, also known as the middle-ear-reflex) even at levels considered quiet when 3k-5k bandwidths are louder than they usually would be in “natural” audio signals. The system is spotting a threat, and it tries to fend it off.[9]

Experiments referenced above (guinea pigs) have also shown that overuse of dynamic range compression can have catastrophic impacts on the auditory components of the mammalian brain stem.

c) Whenever faced with a sound perceived as stressful or threatening (including, but not limited to, “too loud”), the human auditory system activates the so-called stapedial reflex: the tiny muscles in the middle ear contract to block that sound, thus limiting inner-ear exposure to a dangerous stimulus. However, this reflex needs a few milliseconds to kick in (latency).

AI algorithms (and careless sound engineers) that want to increase the “crispness” of consonants in order to “boost speech intelligibility” have ways of making dynamic range compression so aggressive that every consonant becomes a micro-threat to the auditory system. Consonants are rich in high-frequency content and “s” sounds can even reach up to 5kHz. Consonants usually begin with a very short spike in dB level, followed by a sudden drop (a phenomenon known as an “attack transient”). Of course, no natural consonant can rise to its maximum intensity so fast that the stapedial reflex cannot kick in if necessary. Yet, when a digital compressor is programmed in such a way as to cause these spikes to become faster than the stapedial reflex – which is perfectly possible with modern technology – the sudden spikes generated by hundreds of overcompressed consonants per minute, even at supposedly “safe” listening levels, can turn into a flurry of micro-shocks delivered to the softest spots of the inner ear.

A combination of two or more of the above factors is, unfortunately, a frequent occurrence in the videoconferencing and hybrid environment, and constitutes a clear and direct threat to the auditory system and the central nervous system of participants. It is therefore no wonder that autonomic system reactions are detected that would normally correlate with the presence of a threat or of nociceptive stimuli.

The fear subliminally perceived by test subjects in the studies by Riedl, R., Kostoglou, K., Wriessnegger and Wilson and Sasse (see above) is, therefore, real and perfectly justified!

Why overprocess sound?

The point of overprocessing through AI algorithms is to allow people to join a meeting from the street, a noisy train, a windy beach or their car and still be able to make themselves heard. It is also used to purportedly “improve” the low-quality sound made by microphones built into laptop computers. Unfortunately, measurements and experience demonstrate that these “enhancements” come at a very high, but often unnoticed price.

Videoconferencing sound is intrinsically loud, through a particular type of “loudness” that is obtained without exceeding supposedly “safe” levels – a trick already used to some degree in TV advertising. The average dB content of videoconferencing signals is measurably higher than that of “natural” sound, and these signals are inherently noisy and distorted.

To the human nervous system, the voices of videoconferencing participants are virtually screaming with operatic twang, as though they were on digital steroids.

The sources of overprocessing

Overprocessing in the videoconferencing environment is applied by multiple layers of live Digital Signal Processing (DSP) tools. These DSP tools are typically found in:

- the software managing the microphones built into your laptops, telephone, tablet computers;

- the centre-table microphones or microphone arrays your new conference room has been equipped with;

- the call-centre type headset with a boom microphone your employer is asking you to use to “improve” the videoconferencing experience;

- the videoconferencing platform;

The local installation of the room hosting a hybrid meeting.

Given that compressors work logarithmically, each layer of processing added on top of the previous ones boosts them exponentially (compressors work logarithmically), which massively escalates their negative impacts and generates overcompression.

What are the repercussions for human health?

Research has so far mainly concentrated on the impacts of videoconferencing in terms of fatigue, stress and burnout syndromes, but once overprocessed sound is understood as being the chief factor behind this type of fatigue, the link between videoconferencing stress, the auditory “threat” and auditory health problems can no longer be ignored. The following are two examples that clarify this link.

- Digitally overprocessed sound is also a typical feature of call centres. Operators are exposed to aggressive audio signals processed by live digital signal processing devices (DSPs) in more or less the same ways as videoconferencing signals. Unsurprisingly, call centre populations are very exposed to stress, burnout syndromes[10] and typically develop auditory problems like tinnitus, hypersensitivity to sudden noise (hyperacusis), hearing loss and balance problems[11]. Needless to say, these conditions are debilitating, may be disabling, and are usually incurable.

The symptoms reported by call centre operators are usually ascribed to repetitive tasks, multitasking and the assumed presence of sudden loud bursts of noise down the telephone lines – the intensity, the role and even the presence of which has never been convincingly demonstrated. The auditory issues of call centre operators are known in the medical literature as acoustic shock syndrome, but given that the symptoms appear even where sudden peaks of very loud noise are impossible because they are electronically prevented (usually by means, ironically, of … dynamic range compressors!), the very existence of this syndrome has been questioned by some researchers and its definition is controversial.

What no scientific paper on call-centre populations has yet done is characterize and describe the profile of call-centre signals, which, unsurprisingly, are heavily processed by compressors, noise filters and the like to help operators “hear better” and prevent loud peaks.

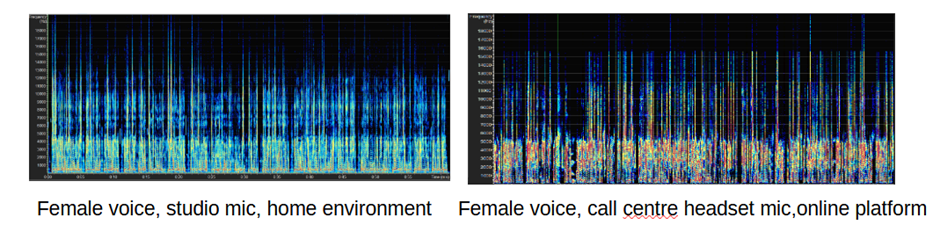

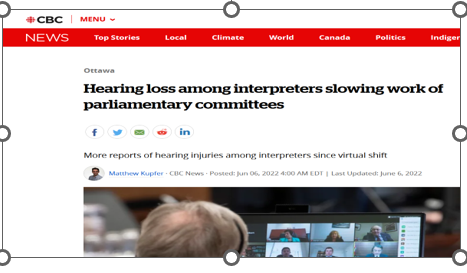

- The introduction of videoconferencing in multilingual and international communication settings (the UN system, the EU institutions, and bodies such as NATO and the Canadian Parliament) etc, and in international business meetings and conferences) where simultaneous interpreters are employed has spawned an unprecedented epidemic of auditory health problems among interpreters[12]. The symptoms are very similar to those already described in call-centre populations. Like call-centre operators, simultaneous interpreters wear headphones. Moreover, they have to listen and speak at the same time, which requires the auditory system to solve a complex puzzle known in the literature as the “cocktail party problem” and are often now on the receiving end of heavily processed sound, picked up (and manipulated by) mobile devices, built-in computer microphones and videoconferencing platforms and then reprocessed by conference room installations that were not originally designed for videoconferencing. Conference room settings often have to be tweaked in order to cater for remote interventions, and many modern installations are no longer manned even by human sound engineers, which further compounds the problem. According to various surveys, over 60% of interpreters working at international organizations have experienced auditory health problems similar to those of call-centre operators since the introduction of videoconferencing in multilingual meetings.

This has made the headlines many times in Canada (where the national parliament is bilingual) and the problem has led to an interpreters’ strike at the European Parliament. Since its first use at the Nuremberg trials, simultaneous interpreting has always been a cognitively intensive task requiring a huge mental effort, frequent lack of eye contact with speakers and abundant frustration, owing to the frequent reading at top of speed of pre-prepared speeches by meeting participants, many of whom are speaking in a non-native language and may be difficult to understand. Significantly though, these stressful factors had never previously led to high incidence of burnout, let alone an epidemic of tinnitus, hyperacusis and hearing loss.

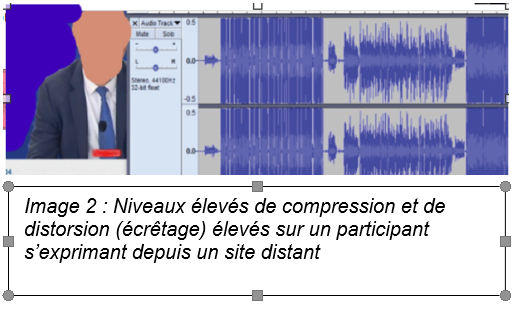

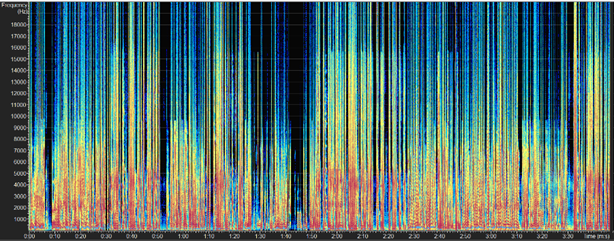

Figure 4: A combination of extremely aggressive compression and equalization during a meeting serviced by simultaneous interpreters

Anecdotal evidence of other categories of workers frequently exposed to videoconferences suggests that the problem might be more widespread. ENT doctors do not typically ascribe these symptoms to poor-quality sound because most of them have no specific training in, or understanding of, sound quality or sound engineering and they have never set foot in a call centre or an interpreting booth. Moreover, such concepts as “toxic sound” and “auditory burnout” do not yet appear in the medical literature, so doctors are typically unaware that poor sound quality is a potential risk factor. A number of teams of researchers are now investigating this, both in Europe and in North America, but evidence of videoconference signals being aggressive and overprocessed is already abundant since it is extremely easy to obtain.

Is every participant in a videoconference call experiencing burnout or auditory health problems?

The impact of overprocessed videoconference audio is obviously not being felt to the same extent by all participants. On the one hand, a certain proportion of the general population is known to be genetically more sensitive to noise and more prone to developing auditory conditions: videoconference signals might simply be driving people whose auditory systems are more fragile “by design” towards collapse. Yet, how many of those auditory systems would develop otherwise rare and disabling conditions like hyperacusis (up to 30% in highly exposed populations) if they were not being aggressively overstimulated by AI algorithms? On the other hand, noise is known to cause harm through prolonged exposure to levels that are not harmful provided that they are limited to 1-2 hours a day. For this reason, regulatory noise limits are always based on daily/weekly doses. Populations with high incidence of disabling auditory symptoms (call-centre operators and, since Covid, interpreters and conference clerks) seem to be concentrated in workplaces where multiple layers of overprocessing can easily be identified. This increases the dose (and makes its content more “toxic”) and it can therefore accelerate the damage-causing process. Workers exposed to videoconferencing in environments where fewer layers of overprocessing are applied might only require more exposure for them to end up having to report to an audiology ward. They might develop fatigue and burnout syndromes before they develop tinnitus. Tinnitus and hyperacusis may also lead to depression and fatigue. Tinnitus can keep sufferers awake at night, while the constant stress generated by the fact that everyday sounds have become harmful and even fear-inducing can take a heavy toll on one’s mental well-being. These symptoms could therefore be viewed as precursors to, or aggravating factors, of depression, fatigue and burnout syndromes.

Finally, it should be borne in mind that not all smokers end up developing lung cancer and not all factory workers exposed to asbestos have developed asbestosis. Risk factors do not necessarily produce negative impacts in each and every subject exposed to them.

Does videoconferencing really increase productivity?

Productivity can be measured in different ways. On a merely quantitative level, replacing face-to-face meetings with videoconferences allows employees and managers to take part in many more meetings than they could attend when Zoom calls were not the norm. However, on a qualitative level, the sorts of results that can be obtained from online meetings hardly compare with in-person interaction: when they are unconsciously feeling threatened and their fight-or-flight mode is activated, participants can hardly be expected to be creative, constructive, empathetic and collaborative. Optimum performance is never achieved (let alone maintained) when people are feeling threatened. Moreover, trust and credibility are key ingredients in any successful team effort or negotiation. An interesting piece of research[13] has recently demonstrated how the degrading of the audio quality of presentations has a major impact on the perceived credibility of the speaker and of their presentations’ contents. In that study, a group of scientists was asked to grade both the personal credibility of fellow scientists presenting their research and the quality of the research being presented. Presentations were recorded, then shown to two different groups of evaluators. Both groups were treated to exactly the same contents, accent, speed of delivery, presenting skills, body language etc.; the only difference was the quality of the audio signal (i.e. the timbre of the presenter), which had been deliberately degraded. It turned out that the group treated to presentations with degraded timbre found the presenters to be less credible and trustworthy and their contents to be of lesser quality. Timbre is the signature of a person’s voice. It reveals the speaker’s inner posture, the amount of tension in the muscles, ligaments and mucosal membranes, and their relative configuration. It is the audible body language of the speaker’s nervous system and inner organs. Timbre indicates to listeners what type of “object” is making a sound, what its shape is and what it consists of. Timbre makes it possible for listeners to distinguish a violin from a trumpet when they are playing exactly the same music. Videoconferencing tools do not distort the speaker’s intonation, rhythm or accent; distortion and spectral manipulation alter the timbre of voices[14].

The reason why degraded timbre has such a huge impact on the credibility of speakers is that human beings tend to be more trusting in people they feel are near to them and similar to them. Timbre contains the spectral cues that allow human beings to establish the distance between themselves and a source of sound. The voices of videoconference participants are typically deprived of part of the frequencies that signal proximity, so they may sound distant even to listeners who are wearing headphones. Alternatively, they may sound so near that they become intrusive, or come across as difficult to place in space (and therefore unreal) because some spectral components are too loud and others too soft. At the same time, most videoconference signals reproduce voices as though speakers had no forehead and no nose and merely consisted, in auditory and perceptual terms, of a neck and an oversized mouth. In real life, no human being sounds like a videoconference participant. Based on what meeting participants sound like online, the deep layers of our nervous system can hardly classify them as real human beings. Moreover, given the way some components of their voices are usually overly boosted, videoconference participants are inherently shouting. To what extent can you subliminally trust someone that looks like a human being, speaks like a human being but does not sound like a human being – and sounds aggressive to your nervous system, to boot?

Given that trust, credibility and rapport are the secret ingredients of every successful human interaction, if any meaningful results are to come out of a meeting videoconference, participants must be able to come across to their counterparts (colleagues, superiors, employees) as credible, authentic and real, and not cause them unwanted and unconscious fight-or-flight reactions.

For an HR manager, making videoconference sound natural could therefore prove to be much more useful than offering staff stress-prevention, conflict-resolution or empathy-based communication training sessions. In the age of videoconferencing, coming across as a real human being is the softest skill your employees can learn.

But can videoconference sound natural? And, if so, how?

The solutions to the problem will be explained in the next edition.

[1] Cranford, S. Zoom fatigue, hyperfocus, and entropy of thought. Matter 3, 587–589 (2020).Wiederhold, B. K. Connecting through technology during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: Avoiding “Zoom Fatigue”. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 23, 437–438 (2020).Riedl, R. On the stress potential of videoconferencing: definition and root causes of Zoom fatigue. Electronic Mark. 32, 153–177 (2022).

[2] Riedl, R. On the stress potential of videoconferencing: Definition and root causes of Zoom fatigue. Electronic Mark. 32, 153–177 (2022).Denstadli, J. M., Julsrud, T. E. & Hjorthol, R. J. Videoconferencing as a mode of communication: A comparative study of the use of videoconferencing and face-to-face meetings. J. Bus. Tech. Commun. 26, 65–91 (2012).

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Media_naturalness_theory

[4] Riedl, R., Kostoglou, K., Wriessnegger, S.C. et al. Videoconference fatigue from a neurophysiological perspective: experimental evidence based on electroencephalography (EEG) and electrocardiography (ECG). Sci Rep 13, 18371 (2023).

[5] Wilson, Gillian & Sasse, Angela. (2002). Investigating the Impact of Audio Degradations on Users.

[6] Dos Santos, T., Bordiga, P., Hugonnet, C., Avan, P., “Musique surcompressée, un risque auditif spécifique”, Acoustique et Techniques, 99, 24-31, 2022.

[7] Rotter K.R.G., Atherton M.A., Kaymak E. and Millar B., Noise Reduction of Dental Drill Noise, Mechanotronics 2008.

[8] Fredriksson S., Hussain-Alkhateeb L., Torén K., Sjöström M., Selander J., Gustavsson P., Kähäri K., Magnusson L., Persson Waye K. The Impact of Occupational Noise Exposure on Hyperacusis: A Longitudinal Population Study of Female Workers in Sweden. Ear Hear. 2022 Jul-Aug 01.

[9] Wiley T.L., Oviatt D.L., Block M.G. : Acoustic-immittance measures in normal ears. J Speech Hear Res. 1987 Jun;30(2):161-70.

[10] https://www.forbes.com/sites/christopherelliott/2023/03/18/thank-you-for-not-calling-agents-are-on-the-verge-of-burnout-study-finds/Toker M.A.S., Güler N. General mental state and quality of working life of call center employees. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2022.

[11] By way of example: Westcott M. Acoustic shock injury (ASI). Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2006 Dec. Pawlaczyk-Luszczynska M., Dudarewicz A., Zamojska-Daniszewska M., Zaborowski K., Rutkowska-Kaczmarek P. Noise exposure and hearing status among call center operators. Noise Health. 2018 Sep-Oct.

[12] Garone, A.: Reported Impacts of RSI on Auditory Health at International Organisations https://drive.google.com/file/d/1OfnkWECRYJgCxNb8jxdVc_tpajMPm5id/view?usp=sharing https://www.acep-cape.ca/en/news/cape-survey-confirms-continued-parliamentary-interpreters-health-and-safety-risks-year https://www.politico.eu/article/strike-european-parliament-interpreters-walk-off-the-job/

[13] Eryn J. Newman and Norbert Schwarz, Good Sound, Good Research: How Audio Quality Influences Perceptions of the Research and Researcher, Science Communication 2018, Vol. 40(2) 246 –257.

[14] More information can be found here: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/does-your-voice-sound-credible-here-why-viewers-switch-andrea-caniato/ and here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZGTjdpZ_Lx8

SCIC: negotiations on working conditions in hybrid meetings

| At SCIC, negotiations on working conditions are underway. For the time being, in line with management’s wishes, negotiations are focusing only on hybrid meetings. Indeed, management wanted to give priority to negotiations on this part of the working conditions, with the aim of concluding them in October 2023. As the rules for hybrid meetings were set in an emergency during the pandemic and as knowledge has progressed since then, it makes sense to review these rules. The Interpreters’ Delegation (ID), as the staff representation, participated constructively in all the meetings and submitted a detailed text proposal at an early stage in the process. It is worth noting, however, that certain factors, such as the frequency of negotiation meetings, are not within the DI’s remit. If the European Parliament (EP) was able to find a solution acceptable to all parties, what are the problematic aspects for SCIC? On the one hand, SCIC has more meetings to cover than the EP, and the diversity of participants is greater. On the other hand, the budgetary resources available to SCIC are inferiour to those of DG Linc in the Parliament. The EP’s solution for guaranteeing good quality sound (sending compliant microphones, testing ahead of meetings, and a team of meeting managers who handle the ‘platform’ aspects during the meetings) is said to be too expensive for SCIC. However, if we put into the equation the savings made by the Commission thanks to hybrid meetings (travel, hotel and per diem costs), it is rather surprising that not even part of this money could be used to guarantee the hearing health of interpreters and participants. In addition, according to SCIC, there seems to be a certain reluctance in the upper spheres of the Commission regarding the system adopted by the EP: the “guarantee to be interpreted only if the equipment and set-up comply“. The reason for this reticence is apparently a so-called democratic deficit due to the link between the compliance with certain rules and the right to be interpreted. However, it is difficult to understand how this health protection measure would be more detrimental to democracy than a badge to access Commission meeting rooms or the fact that for certain languages there is simply no interpretation foreseen in the meeting. As long as good sound quality cannot be guaranteed, hearing health must be protected by limiting exposure. The good news is that it is possible to reconsider exposure thresholds in a responsible way and still satisfy the needs of SCIC. What’s more, limiting exposure will also help avoid that always the same interpreters are exposed to platform meetings. As the risk analysis which the ID had for some time been requesting has finally been announced for January, it would seem wise not to increase the risk before the results of this study are available. Unfortunately, after months of awareness-raising by SCIC, it is a sad reality that at hybrid meetings hardly anyone complies with the microphone recommendations. Contrary to what we thought some time ago, we now know that headsets are to be avoided. Computer and mobile phone microphones as well as wired telephone headsets even more so. A small, compliant microphone can be found in electrical goods stores and on online websites for around thirty euros. A list of compliant and recommended microphones can be found here: |

| It seems that the Commission does plan to send a large number of microphones… to its own staff. This is certainly a nice gesture and should be appreciated. But is this expenditure really well targeted? Shouldn’t priority be given to those for whom it is impossible to come to the meeting room in person? It is definitely a good thing that everybody will have the right equipment for online exchanges, but please, if you are in Brussels, for large meetings with interpretation, COME TO THE MEETING ROOM. You will have no connection problems, you will keep in touch with your colleagues, and you will spare everybody’s ears, interpreters’ and participants’ alike. |

SCIC and DG LINC – a comparison

Eureka! Negotiations at the European Parliament have reached a successful conclusion!

On Monday 25 September, the Joint General Assembly of EP interpreters, and AICs (freelance interpreters) adopted new working conditions for interpreters, including rules for interpreting remote speakers. It took more than a year of industrial action and negotiations between DG PERS, DG LINC, Delint (the European Parliament’s interpreters’ delegation) and the two trade unions that have supported interpreters at the EP, U4U and Ethos, to reach an agreement that comprises working conditions as well as a code of conduct for remote participation in EP meetings. Both are designed to ensure that meetings take place under the best possible health and safety conditions for all. To complete the procedure, the text has still to pass through the Staff Committee and the Bureau of the European Parliament.

As for the working conditions resulting of the social dialogue, they are quite satisfactory – provided that the code of conduct “Requirements for remote participation in meetings of the European Parliament” is effectively put into practice in its entirety. The final text of the working conditions includes a guarantee to this effect: a process aiming at full implementation in the near future is foreseen. In addition, a relevant working group has been set up, which bodes well for the future.

Furthermore, the text on interpretation of remote speakers provides for several exposure limits (2 hours of remote per day, 4 hours per week and a maximum of 4 exceeding the limit of 2 hours per month, which also ensures a fairer distribution between colleagues). In addition, a high compensation (the overrun is multiplied by 3, or even by 4) means that overruns are not attractive for programming. The workload is reduced because of the strenuous character of remote and the additional mental charge it causes. It is adapted thanks to a mechanism that takes into account the actual remote time.

The EP interpreters’ GA adopted the text by an overwhelming majority.

Congratulations on this text, which could serve as a model for the other European institutions!

***

At the Commission, the situation is unfortunately quite different.

Even after the meeting between the Director General of SCIC, the Delegation of Interpreters (DI), the current and previous presidents of the CLP – A. Gonzalez, G. Vlandas, R.Trujillo – as well as C. Roques, Deputy Director General of Human Resources, the social dialogue has not yet allowed the legitimate expectations of staff to be taken into account, and even more worryingly, it has not led to a plan for a structured social dialogue. SCIC is conducting a dialogue of the deaf with the Interpreters’ Delegation and is refusing dialogue with the unions:

The promises made at the meeting have not been put into practice. SCIC is doing everything it can to exclude the elected staff representatives, the DI, from the discussions. For example, SCIC had promised that a mirror committee be set up to define a common approach for the negotiations on the ISO standard defining interpretation hubs. This norm will determine the working conditions of the whole profession in the future. The implication of the voted staff representation is essential. However, SCIC didn’t deliver on its promise.

Also, instead of taking part in the exploratory discussions with the Council on the new Service Level Agreement, the DI may expect merely to be “kept informed”, whereas, given the importance of the subject, its participation – even if only as an observer – is essential.

In addition, in the context of the overhaul of interpreters’ working conditions announced by the administration, SCIC is planning to address topics regarding which it is hard to imagine that a simple “tweaking” of the existing text (the 1987 Agreement and its subsequent updates) would suffice. For anything that goes beyond that, it would be necessary to go back to the level at which the text was negotiated: HR and the unions – with the SCIC administration and the DI as experts. The discussions to come will show whether, in the end, the level chosen is appropriate or whether a change of level will be necessary.

Once again, it seems as if the SCIC hierarchy is trying to sideline the elected staff representatives. SCIC has just created a new functional mailbox to consult interpreters directly on current negotiations. Consulting the rank and file is all very well, but that is the task of staff representation (incidentally already planned and announced), particularly during negotiations. The dialogue is to take place through the structure provided for in the Framework Agreement between the Commission and staff representation, which takes up the Charter of Fundamental Social Rights, incorporated into the Treaty.

We call on the Commission to follow Parliament’s example and organise a genuine social dialogue as soon as possible, instead of bypassing staff representation.

Comission : Resolution of the GA of Interpreters

The General Assembly of staff interpreters of DG SCIC, meeting on 29 September 2023:

A) Notes the request from the Director General of DG SCIC for a recast of the 1987 Agreement on working conditions.

B) Notes the stated objective of the recast not to undermine interpreters’ working conditions, but to find room for simplification and flexibility whilst maintaining good working conditions and work-life balance for interpreters.

C) Expresses the determination to continue providing the high-quality interpretation meeting organizers and conference participants have always expected of DG SCIC and to contribute to DG SCIC remaining both a viable and sustainable public service and an attractive employer.

D) Positively notes that DG SCIC is committed to its duty of care towards its employees and to ensuring a safe and good working environment for its entire workforce, including staff and ACI [1]interpreters.

E) Notes that DG SCIC’s working conditions are already flexible and can lead to a very heavy workload.

F) Believes that our working conditions should be broadly comparable with other international organizations (e.g. UN, EP, CoJ, NATO) and AIC’s rules, and invites DG SCIC to carry out a comparative study of working conditions.

G) Recalls that the nature of the profession confronts interpreters with a series of challenges that need to be adequately accounted for in working conditions for all meeting configurations.

H) Recalls that the cognitive and physical workload for interpreters in meetings has significantly increased since the 1987 Agreement was reached, inter alia due to the spread of “jumbo Councils”, non-oralised presentations of written speeches, greater complexity of topics, video streaming, use of digital platforms, and longer and more irregular meeting hours.

I) Is aware of the fast-paced advances being made by new technologies such as artificial intelligence, but is convinced that quality human interpreting has and will continue to have a crucial role to play in EU decision-making and European multilingualism.

J) Confirms its commitment to integrate new technologies that are safe and fit-for-purpose.

K) Notes that DG SCIC is negotiating an ISO norm on Hubs that will largely determine the working conditions of the future.

L) Mandates the Interpreters’ Delegation as the elected representative of all SCIC staff interpreters to open exploratory talks with DG SCIC about a recast of the 1987 Agreement, according to the principles below:

The recast must:

- Protect the workforce. A sustainable business model for DG SCIC is dependent on healthy interpreters.

- Promote job satisfaction and ensure work-life balance.

- Guarantee appropriate, adapted working conditions for interpreters, which take account of the workload, potential health impacts and additional cognitive load linked to new modes of working and interpreting.

- Further contribute to the established quality of interpretation provided by DG SCIC.

- Be fit for the new working environment with hybrid and remote interpreting settings, so that participants use approved equipment and technical set-up.

- Better acknowledge out-of-booth work activities as part of the workload.

- Include rules on fairer workload distribution.

- Remedy identified shortcomings of the current framework.

M) Takes positive note of the fact that representatives of AIIC will be involved in the talks, with observer status.

N) Takes positive note of DG SCIC management’s commitment to negotiate a new SLA (Service Level Agreement) with the Council of the EU which fully respects our working conditions

O) Requests of its representatives to keep interpreters informed via inclusive and participatory channels, to seek guidance regularly from all booths and to organize a general assembly when necessary. Any partial result of the negotiations will be conditional on the approval of the final package by a referendum, according to the principle that nothing is agreed until everything is agreed.

Changes in the situation of interpreters

New working method for interpreters: how has the situation of interpreters evolved in the different institutions?

At the EP, negotiations on a Code of Conduct, « Requirements for remote participation in EP meetings », and on the incorporation of this new working method into the Working Conditions are continuing.

In principle, the Code of Conduct is definitely a step in the right direction. Based on its raison d’être, the protection of the health of both interpreters and participants in hybrid or remote meetings, it covers the essential aspects of correct remote participation: appropriate equipment (unidirectional microphone), equipment to avoid (headset microphones, Bluetooth microphones, mobile phone wire microphones, built-in microphones of PCs, tablets and telephones), a quality image, a good connection and a calm working environment. All this, plus a sound test.

If this Code of Conduct were mandatory, we could rightly speak of a quantum leap for health and safety in the EP workplace.

Unfortunately, although the recommendations are clear and strong, they are not mandatory. We are left to rely on the common sense and goodwill of MEPs who, we hope, know that the interpreters who have served them faithfully for so many years are not acting on a whim, but are pursuing a more than legitimate objective: the hearing health of all meeting participants.

This lack of a clear framework complicates the negotiations on the integration of remote interpreting into working conditions. How can we define the extent to which we can resort to a work formula if we don’t know exactly what form it will take and with what probability it will be dangerous or not?

Remote interpreting is explicitly described as an “inferior form of simultaneous interpreting” in the IIA-RI (Interinstitutional Agreement on Remote Interpreting, also known as Hampton Court).

Since then, technology has indeed advanced and in recent years we have been virtually obliged to develop this form of interpreting. However, remote interpreting is far from being the same as face-to-face interpreting. From a quality perspective, going on site is always the first option.

The interpreters can see the gestures and facial expressions of the speakers, they can observe everything that is happening in the meeting room, communication is possible between the interpreters and their clients (often by gesture or eye contact, but also by talking to each other), and it is less easy to forget the interpreters when additional documents are distributed.

The absence of these aspects increases the cognitive load. The latter is aggravated by uncertain health protection due to a non-mandatory Code of Conduct. However, a well functioning Code of Conduct is the sine qua non for extending working conditions. Only a transition period that functions as a trial period can guarantee that it works in practice.

If remote only happened exceptionally for very high-level work or in emergencies, that’s one thing. If it is used as the usual mode of presentation, working conditions will suffer. They should therefore be adapted. On the one hand, they should expressly include the “remote” mode of working with all its facets, and on the other hand, something in return should balance out what is in fact a deterioration in working conditions.

Even if there are still important elements to be defined, both in terms of substance and procedure, we are confident that it will be possible to find a solution in Parliament with DG Linc.

At the Commission, we are faced with a problem concerning working conditions in a number of respects and social dialogue, as it is currently being practised, fails to provide a solution.

The area of new modes of interpretation is a huge grey area, with no clear and lasting rules in sight :

– For meetings on platforms, SCIC is still applying the working conditions of the pandemic (IPA) which, moreover, are being applied with a good dose of “creativity”.

For the time being, management is not open to negotiations to find a long-term solution.

At the Council, even for meetings served by SCIC, no set of rules is respected for visioconferences, which are coming closer and closer to remote meetings, which means that the problems of remote access are well and truly present.

– As for hybrid meetings with a low remote participation rate, known as MIPs (Mostly in Person Meetings), a pilot project is underway to collect data. However, what is possible at the EP (collecting data, finding solutions for recording the speaking time of remote interpreters, differentiating the duration of the meeting from the duration of the Interactio connection), seems to be impossible at the Commission.

According to Scic, the data has indeed been collected, but it is unusable. And yet, as a major Interactio customer, SCIC should even be in a position to ask for a technical feature that would make it possible to record remote working time automatically.

The pilot project scheduled to run from October to January has already been extended. As it is due to expire soon, the Interpreters’ Delegation asked what the next step would be. The administration does not seem to be in a hurry to negotiate.

– Regulating platform work in the long term is entirely possible. Working conditions on platforms could even be much more flexible than at present (even though Tempe will always be more strenuous than work on site), provided that good quality sound can be guaranteed. To find a solution to the problem of potentially harmful sound, the EP is working with internationally renowned experts. At the Commission, SCIC did receive the CPPT’s recommendations in February, but the procedure has been bogged down ever since. The Interpreters’ Delegation’s proposals on this subject have not been discussed.

Current working conditions are also suffering :

As a reminder, SCIC was originally conceived as an inter-institutional service for the Commission and the Council. In the end, it became a Commission interpretation service, providing services to the Council, the EESC and the CoR in return for payment.

There is currently a shortage of interpreters on the labour market, which limits the opportunities for SCIC to engage. At present, the Commission is asking for more meetings to be served (which is normal, since it is its interpreting service), so SCIC must provide more resources for the Commission.

At the same time, it does not want to reduce the service provided to the other institutions (on the one hand, it is bound by Service Level Agreements (SLAs), on the other hand, it needs this income, being one of the few DGs that have to earn part of their financial resources themselves).

This situation has several repercussions.

– some of the requests for interpretation (from within the Commission, but also from outside, from the Council and the Committees) cannot be met. The institutions in question therefore try to engage themselves. This is possible, given that they are not bound by the SCIC’s working conditions. We see hourly contracts, contracts for work from home, paid at a rate that is clearly below the rules, and non-regulatory working hours.

Current working conditions are also being eroded.

The workload is distributed very unevenly. The SBC, an purely internal indicator (different from the KPIs for external use) that would help to rebalance the workload, is biased and little used.

Missions are being carried out to impossible timeframes (time to arrive at the airport), and problematic practices are becoming established (Mission Order accepted – but with certain conditions, which means additional costs for the mission leader, without the latter being informed).

At the beginning of May, the SCIC announced that an Action plan to better satisfy demand for interpretation had been drawn up for the coming year. This plan was established without prior consultation of the Interpreters’ Delegation. At a meeting requested by the DI, certain aspects could be smoothed out. The fact remains, however, that a rule concerning extra-statutory work patterns, although recently negotiated, has been further restricted unilaterally.

Compensation for exceptionally long working hours, hitherto decided and when necessary negotiated on a case-by-case basis, has now been fixed as a flat rate without any consultation of the Interpreters’ Delegation. – According to SCIC, the Agreement would allow such a decision to be taken without consulting staff representatives. The ID is still waiting for a precise answer to the question of where such a provision would be found.

In addition, the fixed day for the work of staff representation has recently been called into question. (Until now, Planning had to ask staff representatives for their agreement when it came to giving up their “staff representation” day to work in high-level meetings. In future, the burden would be reversed and it would be up to the DI members to claim it once they see that they are scheduled in a team on an ID-day).

All this does not augur well for the renegotiation of working conditions (the 1987 Agreement and its Annexes which have updated it over the years) which has already been announced for after the summer.

Furthermore, sensible proposals from the Delegation (adapting teleworking abroad to the professional reality of interpreters in a post-pandemic context as well as a feasible solution for the holidays in French speaking Belgian schools) have been brushed aside without any convincing explanation.

While this situation is having an impact on current working conditions, the work of the ISO Group, in which some SCIC representatives (but not staff representatives) are participating, is likely to jeopardise working conditions for the entire profession in the long term. The ISO Group is currently working on a standard governing booths used for a hub. A hub is a working arrangement that separates the meeting room from the place where interpreters gather to work. Since the Commission has no experience of working with a hub, it would make sense to first define the working conditions for this kind of arragnement in the framework of social dialogue, and only then work out the technical aspects of the box (booth) that is supposed to house this type of work.